(deutsche Version nachfolgend)

Our recent event, «Sustainability Talks», attracted around 50 people to Zurich West. Werner Schmidt and Martin Hofer were the invited speakers. They are two different personalities who have long been involved in sustainability issues in the construction industry.

Werner Schmidt began the discussion and explained his path, and sometimes detours, in search of the truly ecological house. He started his career with very diverse projects and approaches, which led him in different directions during his early years of practice. A book about houses made of straw, sent to him by a friend in 2001, was the trigger for his interest in this topic. This was followed by study trips to the US, South America and visits to straw houses in Europe. In 2002 he began experimenting with this building material in the backyard of his office. This was followed by stress tests at the HTW Chur and soon the first project came to life, a single-family house created with load-bearing straw bales. Since then he has built more than 20 projects with a variety of approaches, but all with straw.

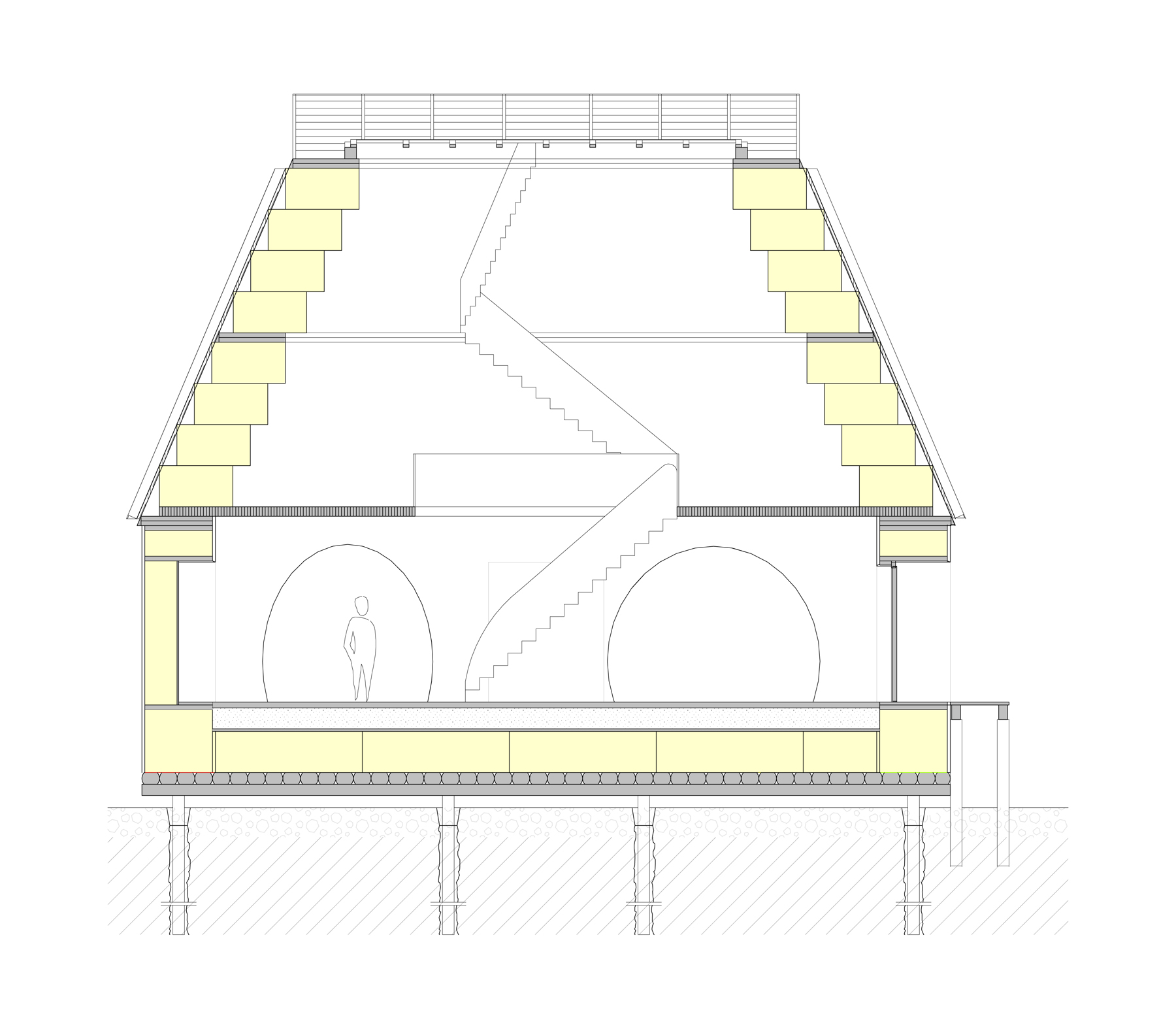

Werner Schmidt continued his presentation explaining the surprisingly simple construction technique he uses. The basement or foundation is conventionally made of concrete to prevent rising humidity. The straw walls are then placed on top of it. In order to accommodate the material compression of 25 to 45 cm of straw bales under pressure, it is important to plan a more or less symmetrical floor layout so that the straw bales compress to the same level on all sides. The ceilings and window reveals are both made of wood in order to spread the load and to achieve the necessary precision for installing windows or doors. After setting the straw bales, they are plastered on both sides with a lime plaster. To minimize or avoid cracks, a metal net is usually installed. Then the only things missing are the ventilated roof, the windows and the doors, and then the house is finished. The extremely low thermal conductivity of the façade, with Lambda values of around 0.045-0.06 W/mK, make it possible for the internal heat sources (occupants, lighting, etc.) to cover 95% of the heat demand throughout the year. For the most extreme cold periods, a wood burning stove is installed or heat is supplied by a solar thermal system.

The construction method using local straw and wood leads to a very good ecological balance over the entire life cycle of the building. In conjunction with the low-energy use, with buildings often entirely self-sufficient, this construction technique leads to an excellent overall energy balance, which far exceeds that of conventional construction methods.

After the break, Martin Hofer analyzed the meaning of our platform’s name, «Atelier for mindful architecture», and the possibility of whether a German word existed with the same meaning. In German one finds exact translations of words such as: attentiveness, awareness, diligence, alertness, intimacy, empathy, but not of mindful. These words may represent different aspects of our core concept, but the English word allows the different terms to be grouped in one term while still remaining open. As a result, he concluded that a translation of the word mindful into German would not have been expedient. Besides, since German words are also adopted in the English language, such as the term zeitgeist, for which no adequate translation is found in English, this too legitimizes applying the English word in German.

Martin Hofer continued with the question of whether we, in Switzerland, live in a mindfully designed environment. His answer and claim that 90% of the settlement area in Switzerland is defaced mindlessly came as no surprise to the audience. With five precise theses he analyzed the reasons for the mistakes repeatedly made in planning.

Much to blame is the lack of education about ‘Baukultur’ (architectural culture, the built environment) within the building community, but also in the general public. Martin Hofer put forward the question of whether architecture, ‘Baukultur’, should betaught in schoolsat a primary level. In the case of architects, a lack of talent is also a relevant factor which exacerbates the problem of missing knowledge. In addition, technocrats (the ‘excel specialists’) aretoo often the decision-makers or controlling power when itconcernsthe built environment. Martin Hofer also put forward the thesis that a lack of mindfulness in architectureis also related to prosperity, specifically the fact that Switzerland is generally a prosperous and comfortable society.

Finally, he shifted the perspective to the future and ended with a positive message. The current generation of younger people, he said, is quite ready to put a conscious, more mindful lifestyle ahead of commercial success.

Note from the author:

Since we did not make any sound recordings, we unfortunately cannot reproduce the theses in their precise construction and complexity. However, the lectures were followed by an animated discussion that lasted well into the night, leaving the memory of a lively evening.

Nachhaltigkeitsgespräche

Der unter dem Namen „Nachhaltigkeitsgespräche“ durchgeführte Anlass lockte rund 50 Personen nach Zürich West. Mit Werner Schmidt und Martin Hofer hatten wir zwei unterschiedliche Persönlichkeiten eingeladen, die sich seit langem mit Themen der Nachhaltigkeit im Baugewerbe beschäftigen.

Werner Schmid begann die Runde und erläuterte seinen Weg, mitunter auch seine Umwege auf der Suche nach dem ökologischen Haus. So begann er seine Karriere mit ganz unterschiedlichen Projekten und Ansätzen, welche in den ersten Jahren in verschiedene Richtungen führten. Ein Buch über Häuser aus Stroh, zugesandt von einem Freund, war 2001 dann der Auslöser für die Auseinandersetzung mit dem Strohballenbau. Es folgten Studienreisen in die USA, nach Südamerika und Reisen zu Strohhäusern in Europa. Im Jahr 2002 begann er im Hinterhof seines Büros selbst mit dem Baustoff zu experimentieren. Es folgten Belastungstests an der HTW Chur und schon bald das erste Projekt, ein Einfamilienhaus erstellt mit lasttragenden Strohballen. In der Folge baute er seit dann bis heute gegen 20 Projekte mit den unterschiedlichsten Ansätzen, jedoch alle mit Stroh. Werner Schmidt erläuterte die überraschend einfache Konstruktion.

Das Untergeschoss oder das Fundament wird konventionell in Beton ausgeführt, um der aufsteigenden Feuchtigkeit vorzubeugen. Darauf kommt das Strohhaus. Um das starke Setzungsverhalten von 25 bis 45 cm der Strohballen in den Griff zu kriegen ist es wichtig, ein mehr oder weniger symmetrisches Grundrisslayout zu planen, damit die Setzung auf allen Seiten das gleiche Mass erreicht. Die Geschossdecken, wie auch die Fenstergewände sind in Holz ausgebildet, um die notwendige Präzision zu erreichen. Nach der Setzung werden die Strohballen auf beiden Seiten mit einem Kalkputz verputzt. Um die Rissbildung zu minimieren, wird normalerweise ein Metallnetz eingebaut. Danach fehlen noch die hinterlüftete Dachhaut, die Fenster und schon ist das Haus fertig.

Die extrem guten Werte der Wärmeleitfähigkeit der Fassadenhülle mit Lambda-Werten von 0,045 – 0,06 W/mK ermöglichen, dass die internen Wärmequellen (Bewohner, Beleuchtung, usw.) ausreichen um den Wärmebedarf zu 95% zu decken. Für die extremsten Kälteperioden wird ein Cheminée eingebaut oder Wärme über eine Solarthermieanlage bezogen.

Die Bauweise mit lokalem Stroh und Holz führt zu einer sehr guten Ökobilanz über den ganzen Lebenszyklus betrachtet. Im Zusammenspiel mit dem energiearmen, oftmals autarken Betrieb führt diese Konstruktion zu einer hervorragenden Gesamtenergiebilanz, die die konventionellen Gebäudehüllen bei weitem hinter sich lässt.

Martin Hofer eruierte nach der Pause die Bedeutung des Namens der Plattform „Atelier for mindful architecture“ und die Möglichkeit, ob nicht auch ein deutscher Begriff der Absicht der Plattform hätte gerecht werden können. Die möglichen Übersetzungen wie: Achtsamkeit, Bewusstheit, Sorgfältigkeit, Wachsamkeit, Innigkeit, Einfühlungsgabe mögen zwar die einzelne Aspekte des englischen Wortes Mindful wiedergeben, jedoch greift das englische Wort Mindful weiter aus, und erlaubt es die verschiedenen Begriffe in einem Begriff zusammenzufassen und gleichzeitig offener zu bleiben. Martin Hofer schliesst demzufolge, dass eine Übersetzung des englischen Wortes nicht zielführend gewesen wäre. Da in der englischen Sprache ebenfalls Wörter aus dem deutschen Sprachgebrauch übernommen werden, wie zum Beilspiel den Begriff Zeitgeist, für den man im Englischen keine adäquate Übersetzung findet, legitimiert dies auch in entgegengesetzter Richtung anzuwenden und ein englisches Wort wie Mindful auch im deutschen Sprachgebrauch zu verwenden.

Weiter führte Martin Hofer mit der Frage, ob wir in der Schweiz in einer „mindvollen“, also achtsam gestalteten Umwelt leben. Seine Antwort und Behauptung, dass 90% des Siedlungsraumes in der Schweiz verunstaltet seien also „mindless“, erstaunte niemand im Publikum. Mit fünf präzisen Thesen analysierte er die Gründe für die Fehlplanungen.

Schuld seien die fehlende Bildung im Allgemeinen und bei den Bauherren. Bei den Architekten käme zur fehlenden Bildung oft auch noch fehlendes Talent. Zudem würde den Technokraten (Excelspezialisten) oft zu viel Macht zuerkannt. Weiter finden sich auch Gründe welche auf die Entwicklung des Wohlstands zurückzuführen sind.

Zum Schluss drehte er die Perspektive mit Blick auf die künftige Generation wieder ins Positive. Diese Generation, so führte er aus, sei durchaus bereit den kommerziellen Erfolg einem bewussten Lebensstil hintenanzustellen.

Anmerkungen des Autors:

Da wir keine Tonaufnahmen gemacht haben ist es uns leider nicht möglich die Thesen in ihrer präzisen Konstruktion und Komplexität wiederzugeben. Den Vorträgen folgte aber eine angeregt geführte Diskussion, welche bis tief in die Nacht hinein reichte und es bleiben die Erinnerung an einen lebendigen Abend.