(deutsche Version nachfolgend)

The recent demand for sustainable buildings has brought earth building back into focus. Hip builders and architects are breathing new life into the 10,000 year old building material. But what is earth building actually all about? What is the potential of building with adobe? We asked Martin Trueb these questions, a Swiss architect who emigrated to Portugal 30 years ago and has been building with adobe ever since.

His way to earth building

Martin started his architecture office in Vila Nova de Milfontes in the south of Portugal about three decades ago. Instead of simply applying what he had learned at the ETH in Zurich, his interest in the local building tradition led him to earth building. What began as curiosity led to an intensive examination of the building culture and, ultimately, to a passion for the material.

While the houses in the north of Portugal are made of natural stone, earthen structures have been built in the south for centuries. The knowledge of how to build with adobe originally came from North Africa, where this method of building has been widespread for thousands of years. Portugal’s south, a hot and dry climate zone, is ideally suited for this type of construction, as the high mass of the adobe walls stores the temperature and gradually releases it to the interior.

Fascinated by the building tradition and the material, Martin looked for construction companies in the area that knew how to build adobe houses. This was not an easy task, as the idea of modern living with brick and concrete had almost completely displaced the earth building tradition. However, he managed to find construction professionals who had built with adobe in their youth and who still remembered how it was done. With this local knowledge he set about building his first projects with rammed earth.

The building process

The greatest challenge of earth building is to control the shrinkage when the material dries out. For his first projects, Martin sent soil from the property to a laboratory in Lisbon in order to better assess the load-bearing capacity and properties of the building material on site. However, he has long since done without laboratory analysis and nowadays makes practical experiments on site that provide much more precise information about the properties of the earth. There seems to be no one valid type of mixture, as the earth reacts differently depending on where it comes from, and so, the practical load experimentation with blocks leads to a much more precise approximation of the actual properties.

The primary building material is a mixture of soil extracted from the property. This top layer may well contain dry roots and grasses. Stone flour is added to the mix, which reduces shrinkage when it dries out. Enriched with water to form a moist but loose soil mixture, the material is applied in layers. Two wooden boards serve as formwork, and compacting is done by hand with a wooden stick with a wedge-shaped thickening at the end. Attempts to perform the compression mechanically have not lead to comparably good results, as compacting by hand allows feeling when the material has reached the required density. The disadvantage of this type of construction is the amount of manual work required and the correspondingly long time needed. In addition to the construction time, adobe walls need two to three months to dry out and carry loads. Other physical properties, such as moisture diffusion, acoustic and thermal insulation, are fully guaranteed after about four to five months, depending on the weather. The building project is, therefore, best planned so that the drying time falls in the hottest season. In order to meet the legal requirements for thermal insulation and to meet today’s comfort standards, the adobe walls are built with a thickness of 50 to 70 cm, depending on the location. In addition to the aesthetic elements, in which the manual work and the different colors of the earth remain visible, the good indoor climate properties, such as good room acoustics and humidity regulation, are arguments in favor of earth building. The thick outer walls also offer the possibility of inserting shutters or radiators as niches in the wall.

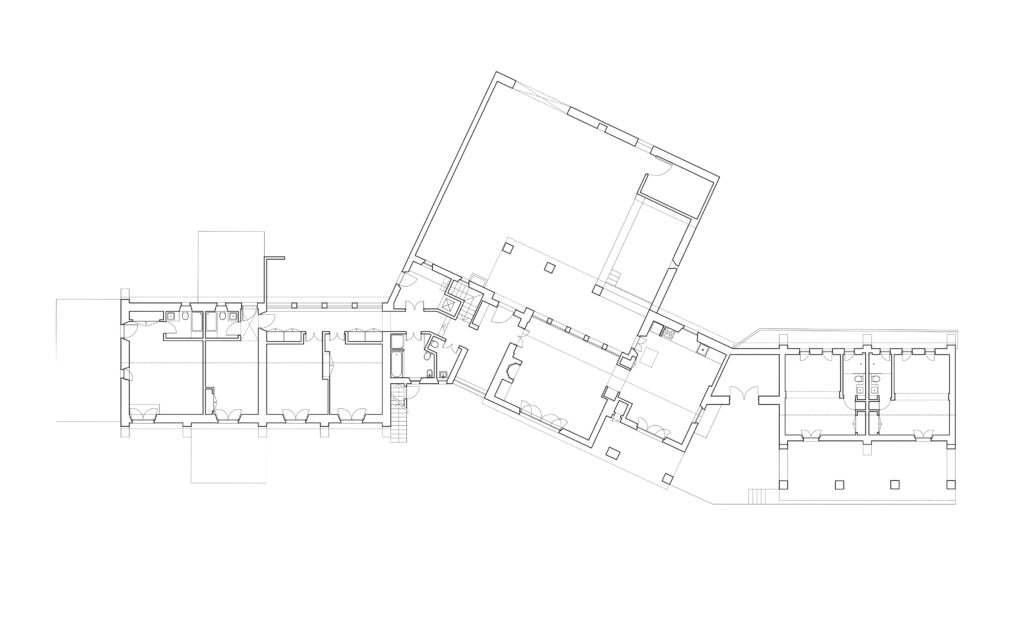

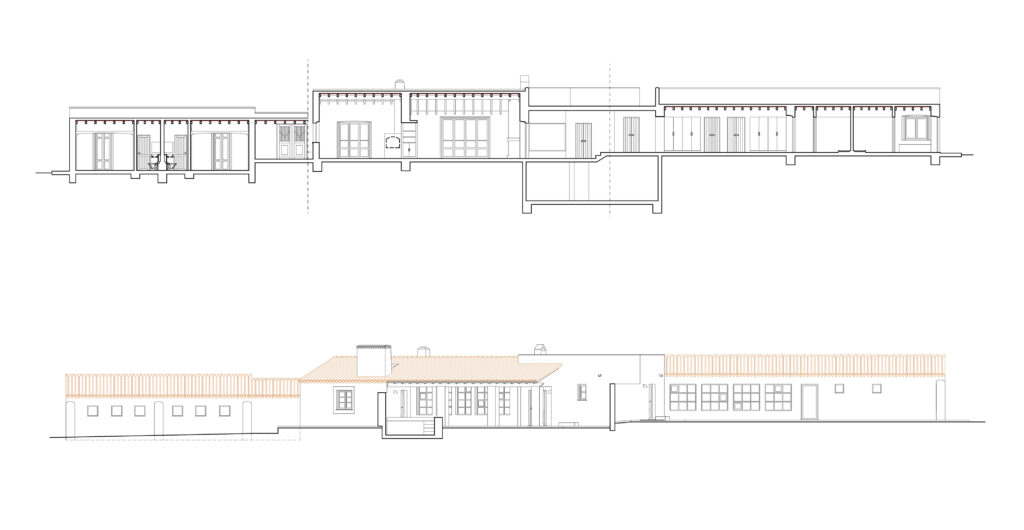

The use of adobe shapes the architectural expression of the building. Small openings for windows and doors are primarily used so that the adobe walls do not lose their load-bearing function. In the traditional single story houses with earth walls, triangular struts, so-called «contrafortes», were attached to the corners of the building and in the middle of long walls, to absorb the shear forces generated by the roof.

Coating the walls with lime plaster serves as additional weather protection, but this can be avoided by using a large canopy. In traditional houses no value was placed on showing the earth building, while today, and mostly for aesthetic reasons, the earth often remains unplastered and visible as a building material. Only the weak points of the wall, the edging of the building and the edging around the window openings, are plastered.

In contrast to the traditional single story houses with load-bearing earth walls, Martin frequently uses a mixed construction method, that is, the earthen construction walls serve only as outer walls, while a concrete skeleton supports the roof. This means that the external struts can be dispensed with and larger wall openings can be created. The floor slabs are made in concrete to prevent humidity from rising. In line with traditional buildings, Martin often uses a roof structure consisting of wooden beams with «canas» on them, dried reeds, 6 cm cork panels made of pressed cork granulate, and a sub-roof that is covered with tiles.

Sufficiency

Martin Trueb reveals that he is not a radical advocate of earth building. He has always used adobe, or rather rammed earth, only if it is available on the property and does not have to be transported. What was obvious to him 30 years ago is now called gray energy reduction. While the youngest generation of architects is committed to radical earth building, Martin continues to build in the most reasonable, sensible way for him and the environment. This means real sustainability, building with natural local resources and achieving a maximum reduction in emissions, precisely what we owe the next generations. Text: Markus Elmiger 2022

Mit der Erde bauen

Die Forderung nach nachhaltigen Gebäuden rückt den Lehmbau seit kurzem wieder in den Fokus. Hippe Bauherren und Architekten erwecken den 10’000 Jahre alten Baustoff zu neuem Leben. Aber was hat es mit dem Lehmbau tatsächlich auf sich? Was sind die Potenziale mit Lehm zu bauen? Diese Fragen stellten wir Martin Trueb, einem Schweizer Architekten, der vor 30 Jahren nach Portugal auswanderte und seither mit Lehm baut.

Sein Weg zum Lehmbau

Martin eröffnete vor ca. 3 Jahrzenten sein Architekturbüro in Vila Nova de Milfontes im Süden von Portugal. Anstatt einfach anzuwenden, was er an der ETH in Zürich gelernt hatte, war es seine Neugierde für die lokale Bautradition, was ihn zum Lehmbau führte. Was als Kuriosität begann, führte zu einer intensiven Auseinandersetzung mit der Baukultur und letztendlich auch zu einer Passion für das Material.

Während im Norden von Portugal die Häuser aus Natursteinen gebaut sind, wurden im Süden seit Jahrhunderten Lehmbaukonstruktionen erstellt. Das Wissen wie man mit Lehm baut kam ursprünglich aus Nordafrika, wo diese Bauweise seit Jahrtausenden verbreitet ist. Portugals Süden, eine heisse und trockene Klimazone, eignet sich hervorragend für diese Bauweise, da die hohe Masse der Lehmwände die Temperatur speichert und zeitverschoben an den Innenraum abgibt.

Fasziniert von der Bautradition und dem Material suchte Martin in der Gegend nach Bauunternehmungen, die wussten wie man Lehmhäuser baut. Dies war gar nicht so einfach, da die Vorstellung vom modernen Wohnen mit Backstein und Beton die Lehmbautradition fast gänzlich verdrängt hatte. Jedoch gelang es ihm Baufachleute zu finden, die in ihrer Jugend Lehmbauten erstellt hatten und sich daran erinnerten wie man mit Lehm baut. Mit diesem lokalen Wissen machte er sich daran, seine ersten Projekte mit gestampfter Erde zu bauen.

Der Bauprozess

Die grösste Herausforderung des Lehmbaus ist es, das Schwinden beim Austrocknen in den Griff zu kriegen. Bei seinen ersten Projekten sandte er jeweils ein Stück Erde des Grundstücks in ein Labor nach Lissabon, um die Tragfähigkeit des vorhandenen Baumaterials und die Eigenschaften besser einschätzen zu können. Wie Martin im Gespräch ausführt, verzichtet er inzwischen schon lange auf die Laboranalyse und macht praktische Versuche vor Ort, die viel genauer Auskunft über die Eigenschaften der Erde geben. Es gibt scheinbar keinen gültigen Mischungsmix, da die Erde, je nachdem woher diese stammt, unterschiedlich reagiert und so der praktische Versuch mit Blocks, welche belastet werden, zu einer viel genaueren Annäherung der effektiven Eigenschaften führt.

Gebaut wird mit einem Gemisch bestehend aus auf dem Grundstück abgebauter Erde. Es handelt sich dabei um die oberste Schicht, welche durchaus trockene Wurzeln und Gräser enthalten darf. Dazu wird Steinmehl beigegeben, welches das Schwinden beim Austrocknen reduziert. Mit Wasser zu einer feuchten aber lockeren Erdmischung angereichert, wird das Material in Schichten eingebracht. Zwei Holzbretter dienen dabei als Schalung, verdichtet wird von Hand mit einem Holzstock mit einer keilförmigen Verdickung am Ende. Versuche die Verdichtung mechanisch auszuführen, führten nicht zu vergleichbar guten Resultaten. Offenbar fühlt man bei der Verdichtung von Hand, wann das Material die geforderte Dichte erreicht. Der Nachteil dieser Bauweise ist, dass relativ viel Handarbeit anfällt und dies entsprechend viel Zeit erfordert. Neben der Zeit für die Erstellung benötigen Lehmwände zwei bis drei Monate bis sie ausgetrocknet sind und Lasten aufnehmen können. Weitere bauphysikalische Eigenschaften, wie Feuchtigkeitsdiffusion, akustische und thermische Isolation sind, je nach Witterung, nach etwa vier bis fünf Monaten voll gewährleistet. Das Bauvorhaben plant man daher am besten so, dass die Austrocknungszeit in die heisseste Jahreszeit fällt. Um die gesetzlichen Anforderungen bezüglich Wärmedämmung zu erfüllen und den heutigen Komfortansprüchen zu entsprechen, baut man die Lehmwände je nach Ort mit einer Dicke von 50 bis zu 70 cm. Neben den ästhetischen Elementen, bei denen die Einbringung von Hand und die verschiedenen Farben der Erde sichtbar bleiben, sind auch die guten raumklimatischen Eigenschaften, wie gute Raumakustik und Feuchtigkeitsregulierung, Argumente, die für den Lehmbau sprechen. Die dicken Aussenmauern bergen weiter die Möglichkeiten Fensterläden oder Heizkörper als Nischen in der Wand einzulassen.

Die Verwendung von Lehm prägt den Gebäudeausdruck. Damit die Lehmwände ihre Tragfunktion nicht verlieren, benutzt man eher kleine Öffnungen für Fenster und Türen.

Bei den traditionellen eingeschossigen Häusern mit Erdwänden wurden aussen dreieckige Verstrebungen, sogenannte «Contrafortes» in den Gebäudeecken und in der Mitte von langen Wänden angebracht, welche die vom Dach entstehenden Schubkräfte aufnehmen.

Das Verputzen der Wände mit einem Kalkputz dient als zusätzlicher Wetterschutz, darauf kann aber durch ein grosses Vordach verzichtet werden. Bei den traditionellen Häusern wurde kein Wert daraufgelegt, den Lehmbau zu zeigen, während in der heutigen Anwendung und eher aus ästhetischer Überlegung der Lehm oft als Baumaterial in der Mauer unverputzt und sichtbar bleibt. Nur die Schwachstellen, die Umrandung des Gebäudes sowie die Umrandung um die Fensteröffnungen werden verputzt.

Im Unterschied zu den traditionellen eingeschossigen Häusern mit tragenden Erdwänden, benutzt Martin Trueb heute oft eine Mischbauweise, das heisst die Lehmbauwände dienen nur als Aussenwände, ein Betonskelett trägt das Dach. Dadurch kann auf die äusseren Verstrebungen verzichtet und grössere Wandöffnungen erstellt werden. Die Bodenplatten werden in Beton erstellt, um aufsteigende Feuchtigkeit zu vermeiden. Als Dachkonstruktion verwendet Martin oft, wie bei den traditionellen Gebäuden, eine Konstruktion bestehend aus Holzbalken, darauf «Canas», ein getrocknetes Schilfgras, 6cm Korkplatten aus gepresstem Korkgranulat, und ein Unterdach, welches mit Ziegel eingedeckt wird.

Suffizienz

Martin Trueb betont kein radikaler Verfechter des Lehmbaus zu sein. Er benutzt den Lehm, oder besser gesagt die gestampfte Erde nur, wenn diese auf dem Grundstück verfügbar ist und nicht hergeschafft werden muss. Was für ihn bereits vor 30 Jahren eine Selbstverständlichkeit darstellte, nennt man heute Verringerung der grauen Energie. Während die jüngste Generation von Architekten sich nun dem radikalen Lehmbau verschreibt, baut Martin weiterhin mit den für ihn vernünftigsten und sinnvollsten Mitteln.

Dies heisst wirklich nachhaltig, mit lokalen natürlichen Ressourcen eine höchstmögliche Reduktion von Emissionen zu erreichen, eigentlich genauso, wie wir dies der nächsten Generation schulden. Text: Markus Elmiger 2022